Just you

1860-1929

The Birth of BC Electric

The Birth of BC Electric (1860–1929)

Every era lays claim to fame through earthshaking events, remarkable individuals, and new ideas. But, by any standard, the seven decades that began with the introduction of gaslight to this province in 1862 and ended in 1929 when the British Columbia Electric Railway Company (BCE) was “brought home” from England were remarkable. In 1867, a new country called Canada was created, followed by a new province, British Columbia. Since neither the transcontinental railway nor the Panama Canal had been built at the time, it took months to get news or goods from Eastern Canada or Europe. The province was virtually cut off from the rest of the country. Seventy years later train lines, highways, and a budding airline industry connected the country. For most of this period, women and many ethnic groups couldn’t vote. The First World War employed weapons of unimaginable destructiveness and was not truly won by any side. Transportation was no longer typified by beasts of burden but by new electrical and combustion systems. And, during these 70 years BC Hydro’s largest predecessor was born. Created in 1897, BC Electric was preceded by various utility companies that produced power, lit streets, heated homes, and ran streetcars. At first, the new company did three jobs: generate and sell power, manufacture and sell gas, and run transit systems. Its markets were Vancouver and Victoria.

As the population grew, so did the company and the services it offered. So, by 1929, BC Electric was firmly established in the economy of BC and — for better or for worse — in the consciousness of its citizens. Although the company provided many excellent services and played a leading role in modernization, it was still a private utility operating on a for-profit basis. Plenty of people saw BC Electric as the big, bad utility. Some things never change.

In the rest of the province, power and transit remained local affairs — when they were available at all. In 1910, some 38 communities were served by utilities of one sort or another; 20 years later, 118 communities throughout BC had power and BCE and the West Kootenay Light and Power Company ran major hydroelectric generating facilities in Vancouver, Victoria, and the Kootenays.

During its first three decades, BC Electric grew and improved through the efforts of its employees, many of whom spent their entire careers with the company. They believed they were providing good service — and they were. These were the original power pioneers who laid the groundwork for the future.

The illustration below from the late 1920’s shows BCE’s various operations: gas, electricity generation and transit. A streetcar motorman is on the right, and line workers with their distinctive felt hats are on the left.

And Then There Was Gaslight…

In early colonial days, gas manufactured from coal provided both domestic and street lighting. The first gas lighting appeared in Victoria on September 28, 1862, provided by the Victoria Gas Company. The Colonist headlined the story “Gas At Last!” and reported:

Yesterday at three o’clock, Mr. Murphy, Manager of the Gas Works, filled three of the retorts and commenced the Generation of Gas… Mr. Murphy expects to light gas, for the first time in the city, at eight o’clock tonight, in front of Carroll’s liquor store on Yates Street; and several stores will be lighted tomorrow evening.

Gaslights, it was hoped, would replace whale-oil lamps and tallow candles. But gas did not cast a particularly bright light. Its performance improved greatly about the turn of the century, but not enough to stop the swing to electricity for lighting-once electricity overcame its own teething troubles. However, gas continued to be promoted for heating and cooking, as it is today.

At the start, the gas distribution system was confined mainly to the downtown area of Victoria and its neighbourhoods. Customers were almost all commercial establishments, such as the ubiquitous saloons, but some street lighting also appeared. For many years the streetlights were turned off at 12:30 a.m., when honest citizens were presumably safely home in bed. By 1887, Vancouver and New Westminster also had gas for lighting.

The first gas appliances were simple. They included space heaters that were little more than tin boxes hooked up to the nearest gas jet by a rubber hose. Stoves were larger but also basic.

In the early days, manufacturing gas was a primitive business. Workers pushed wheelbarrows of coal and shovelled it into retorts by hand. (Cranes were an unheard-of luxury.) Pulverizing and distilling the coal and then extracting gas was laborious and dirty work, and the final product was somewhat unstable and dangerous. Once manufactured, gas was piped underground to streetlights and to the few homes that used it for cooking or heating.

Gas fitters, who maintained the gas distribution system, were supplied with a horse and carriage for the job. T. R. Meyers was a long-time BCE employee who wrote for and edited many company publications including an unpublished book, 90 Years of Public Utility Service on Vancouver Island. Meyers wrote about the gas fitters’ work in the BCE Employees’ Magazine.

The early gas meters were of the “wet” variety. A certain amount of water had to be maintained in the meters or they would not work. Early gas meter readers carried a water can with a long spout in one hand and very often a coal-oil lantern in the other to enable them to read the meters in the dark cupboards and cellars in which they usually were placed. Whether Victoria had colder winters in those days or the meters were placed in unusually exposed positions is not clear. Anyway, these wet meters were likely to freeze in winter weather. This not only meant the meter might split, it would also effectively cut off the supply of gas. Customers were warned on the bill that this freezing possibility was strictly their headache. It advised this: that it could be overcome by adding alcohol to the water in the meter. If alcohol were not available, it was suggested that a good grade of Scotch whisky would do just as well.

Over the years, the Victoria Gas Company improved production and expanded distribution. However, gas lamps, especially for public lighting, were still not effective and safety was a continuing concern.

Early Electricity

In 1883, an enterprising Victoria citizen named Robert McMicking contracted with the city council to erect tall masts carrying clusters of arc lamps at three central downtown intersections. Power came from a 25-horsepower steam engine manufactured by the Albion Iron Works. City councillors were invited to judge the illumination by standing beneath a pole and reading their newspapers. They did so, and returned to City Hall to vote for the new lighting system.

However, McMicking had an uneasy relationship with the city over the next decade, largely because the system always seemed to need expensive upgrading. Still, he wasn’t one to waste taxpayers’ money, as the Colonist reported.

Victoria was plunged into darkness last night when the dynamos which run the local plant were turned off by Mr. McMicking. A reporter of the Colonist was sent down to the Pound office where the dynamos are located and asked the reason for the sudden closing down. Mr. McMicking replied that the moon was up and therefore no electric light was necessary. The Colonist is of the opinion that the lights should remain on all the time.

The next market for electrical entrepreneurs was interior lighting. However, the first electric lamps also had their limitations, as might be indicated by their nickname, “glow worms.” The arc lamps that replaced them sputtered, and the first incandescent lamps, in turn, were very fragile.

Electrical companies tried to sell power to municipal authorities first, which wasn’t always easy, as promoters of the new Vancouver Electric Illuminating Company found in 1887. Having built a steam-fired generating plant at the corner of Pender and Abbott Streets, they attempted to promote its potential by installing a 16-candlepower light in the city council chamber on Powell Street. Decades later, an article in BC Hydro’s Intercom magazine described what followed.

Some aldermen were skeptical… One of them in particular, Alderman Humphries, was much opposed to any newfangled notions and was prepared to squash the proposal.

When the electric light was turned on, he produced a common tallow candle and, striking a match on his pants, lit the candle and then, proudly holding it up to the electric lamp, said: “Mr. Mayor, they call this thing they want to plant on us 16 candlepower. I call it a swindle. I don’t see any improvement in it over this single candle.”

Fortunately, more progressive minds prevailed and a contract was signed.

There was soon little doubt about the potential of electricity if all the elements of a system, including transit, could be brought together.

About 1890, promising efforts to extend and promote domestic electrification were made in the capital by the Victoria Electric Railway and Lighting Company and on the mainland by the Vancouver Electric Railway and Light Company. But unreliable lamps, poor wiring, and an inadequate power supply made the going difficult. New Westminster built its own municipal electrical power station in 1890. The Westminster and Vancouver Tramway Company completed a New Westminster powerhouse in 1891, followed by a Burnaby powerhouse in 1892. How-ever, the depression of 1893 left the three private companies bankrupt.

Lake Buntzen Power Plant Centenary 1903 – 2003

December 2003 marks the centenary of the Lake Buntzen Power Plant, the Lower Mainland’s first hydro electric generating station. The year 1903 was one of many important developments; the founding of the Ford Automobile Company; the Buick Motor Company; the Harley-Davidson Motor Cycle Company; and on December 17, 1903 the Wright Brothers successfully achieved the first heavier than air powered flight. On this same day, the first unit of the then Trout Lake Power Station (after 1905 Lake Buntzen) started and produced the first hydro electric power in the Lower Mainland of B.C. Two days later, on December 19th, the City of Vancouver was first lit by water power. The Province newspaper of the day printed an article titled “Steam discarded in favour of Water Power”. Prior to 1903, the electricity used to power the streetcars, interurbans, lighting, as well as power industry in the area came from a thermal electric plant located at Prior and what is now Main Streets in Vancouver. This plant was aided by a small steam plant in Burnaby near the present Newell Substation.

The growth in the demand for power in the early years up to 1913 rose as high as 30% per year. The B.C. Electric Company, through its predecessor companies had sought to find local sites for a water plant to produce electricity. In 1891 the North Vancouver Power Company proposed a plant on the Capilano River (the site is now the park along the river). In 1895 the Consolidated Railway Company planned and called tenders for the construction of a plant on the Seymour River. A survey authorized by this company in 1896 of the power potential of the Lake Coquitlam and Stave Lake, was inherited by the B.C. Electric Railway Company after its incorporation in April, 1897 to assume control of the assets of the Bankrupt Consolidated Company. Due to a technical problem with the wording of the Provincial Consolidated Water Clauses Act of 1897, the B.C. Electric had to create a subsidiary company, The Vancouver Power Company on January 28, 1898 in order to build a water power plant.

The Vancouver Power Company decided the Lake Coquitlam site was superior to the other available power sites. The proposal initially called for the building of a five mile long flume and ditch to carry Lake Coquitlam water to sea level at Port Moody. In an 1898 report presented by the engineering firm of Garden, Hermon and Berwell, it was noted that there was only a 2 1/2 mile wide ridge separating Lake Coquitlam from what was then two lakes, Trout and Lake Beautiful (in 1905 to become Lake Buntzen). The engineers suggested a tunnel be blasted through the ridge and a dam at the outlet of Trout Lake be constructed to allow the lake to be used as a forebay for a sea level power plant located 400 feet below the lake.

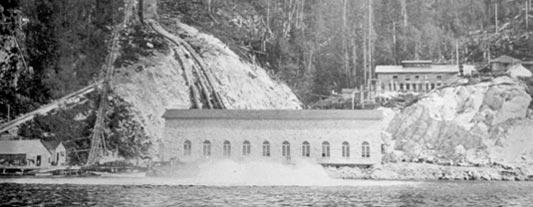

The first step in the process of beginning the project was the acquisition of land and water rights to Lake Coquitlam and Trout Lake. Active negotiations began in early 1900 and due to stiff opposition from citizens of New Westminster who’s water supply came from Lake Coquitlam, and from the proponents of the Stave Lake power proposal, permission to begin construction was not granted until early 1902. Construction of the camp facilities at what was to become Buntzen Bay began in February 1902. By June construction had begun on the sites of the Power House, Trout Lake Dam, the grading for the pipeline-penstocks and the Lake Coquitlam-Trout Lake Hydraulic tunnel. The plan for the Power House called for a building capable of holding ultimately four units, each of 3,000 horsepower and producing 1,500 Kilowatts of power. The building was to be of solid masonry construction with walls 3 feet thick, 90 feet high at the peak of the roof, 34 feet wide and 156 feet long.

The machinery for the plant was to consist of water wheels from the Pelton Company of San Francisco and the generators, exciters, transformers and control panels from Westinghouse. The voltage generated was to be 2,000 volts with the transformers, housed in a reinforced concrete building adjacent to the power house, upping the voltage to 20,000 volts. The Trout Lake Dam was constructed of reinforced concrete with a height of 53 feet, a length of 360 feet, and a width at the base of 15 feet topping at 7 feet. Though only one pipeline of 54 inches in diameter and 1800 feet long was to be placed in the initial installation, the bellmouths and valves for the full ten units as well as the two exciters were placed in the concrete of the dam. The first 800 feet of the pipeline was wooden while remaining length was boiler plate which gradually reduced from 54 inches to 42 inches at the Power House. The exciter pipeline was 24 inches in diameter and made entirely of boilerplate.

The power from the Lake Buntzen Power Station was carried to Vancouver through a pole line 17 miles long and which crossed Burrard Inlet at Barnet Beach on two steel towers. The southern tower was 140 feet high and the northern tower built on a high bluff was 60 feet high. The clear span between the towers was 1/2 mile in length and was 200 feet above the water of the inlet. Two wooden poles followed the Barnet Wagon road to the Pole Line Road (now Sperling Avenue), with one reaching Vancouver via Hastings St. to the newly built Vancouver Sub- station and the other line built south along the Pole Line Road to the Burnaby Substation, at the site of the old Burnaby thermal electric plant and tram barn.

The Buntzen Power Plant produced its first power on December 17, 1903 and as mentioned earlier, supplied water power to Vancouver two days later. The project was initially to cost $800,000 but ended up costing $1,200,000. The demand for power increased so rapidly over the next few years that by 1906 the fourth unit originally planned for the existing Power House was installed. Three more units of increasingly larger types were installed over the years to January 1912.

Due to problems with foundations, the remaining three units were installed in a new plant (Buntzen #2) located 1/2 a mile south of the old plant. Between 1909 and 1911 the water tunnel between Lake Coquitlam and Lake Buntzen was enlarged from 9 feet by 9 feet to 14 feet by 14 feet to allow the installation of the final three units. This also required the rebuilding and replacement of the original 15 foot high log crib Lake Coquitlam Dam with an 85 foot high hydro filled (water washed sand and gravel) dam with a water proof clay core and rock covered surface. A water gate (tower) was installed to provide water to New Westminster and a sluice gate (tower) to lower the level of the Lake when required. The dam was completed in January 1914. Due to the economic downturn in 1913, which reduced the demand for power, the tenth unit did not have its pipeline assembled to allow its use until 1919. This marked the end of the original building program.

The style of machinery available for power production in 1903 to 1913 required people to operate and maintain them. This resulted in a small community being developed above the Power House on the steep slopes of the hillside. Over the nearly 50 years the original plant produced power (1903 to 1950) families would be located at the site and endure the rainy, foggy weather, lack of flat ground and the need to leave by boat to seek groceries, medical attention and any form of entertainment not satisfied by tennis, badminton or fishing. One lady who resided at Buntzen from 1937 to 1943 and raised two children there commented that dogs and woman had to leave Buntzen before 10 years or they would become bushed (a little odd).

In 1950 the original four unit Power House was demolished by a planned explosion (it took two tries as the old time builders had constructed the three foot thick walls to last). The last three units of the old Buntzen #1 Power Plant were replaced in 1951 by a single unit which produced nearly three times the Power of the seven old units. This new unit was capable of being operated by remote control, thus the people were no longer needed and by 1964 when Buntzen #2 ceased regular operations, the community had begun to decay into the soil of the rain forest it was located in. The old Trout Lake Dam was the next to be replaced, being reconstructed to 57 feet in height in 1965. In 1971, the area around the reservoir became a recreational area. Between 1980 and the mid 1990’s, upgrades were effected on the Lake Coquitlam Dam. The two towers carrying the transmission cables across Burrard Inlet at Barnet Beach were replaced in 1989, not due to structural defects but because of a concern regarding earthquake proofing.

Today the Lake Buntzen Power Plant produces less than 0.4% of the power produced by the generating facilities owned by B.C. Hydro. However it has the distinction of being the first hydroelectric generating plant to supply the Lower Mainland of B.C. In the early years it was considered to be an engineering marvel and after nearly 100 years still produces inexpensive power.

The use of Lake Coquitlam water has changed over the last few decades as the Greater Vancouver Regional District draws more and more water from the Lake to supply drinking water for the regions growing population. The first plan to use the water of Lake Coquitlam was by the Coquitlam Water Works Company in 1885. The plan called for a pipeline to serve Vancouver, Burnaby and New Westminster. The B.C. Electric purchased the company in 1902 to use the water rights for power production. However, the plan to supply the region with drinking water developed nearly 120 years ago was achieved this year with the completion of a 60 inch pipeline from Lake Coquitlam to the Little Mountain Reservoir in Vancouver. By the year 2050 it is suggested that all the water from Lake Coquitlam would be required for drinking water supplies with little left for power generation. But by then the 1951 Buntzen #1 replacement, if it has not itself been replaced will be nearing its’ centenary. Buntzen #2 with two of the three original 1913 Doble water wheels and Dick-Kerr generators is the oldest still operational plant in the B.C. Hydro system. Unlike the newer plants, Buntzen #2 still has its’ exciters which are used to energize the main generators, and this enables the plant to do a black start should there be a system wide failure as experienced in Easter Canada and the United States earlier this year.

The use of power produced has changed over the last century. In 1903 95% of the electric energy was sued for the streetcar and interurban lines (transit) with the remainder split between street lighting, industry and a very small amount for lighting in homes. As the use of electric powered household appliances became more common, the split between transit and other uses changed. By the 1920’s it was nearly half-and-half. Today 95% plus of the electrical energy generated in the province goes to industry and home use, with very little to transit.

As the Lake Buntzen Power Plant nears the date of its’ centenary in December 2003, the plant, the company and the people who built and operated the facility for nearly 50 years can look back at a job well done, of supplying dependable power inexpensively. Though the Plant has been overshadowed by the giant new plants like Shrum in the Peace River area and Mica in the Columbia River area, it still has the distinction of being the first to serve this area and for a century has done a good job.